I am not a crier. Not at movies, and certainly not at books. The first and last time a book made me cry was in the second grade, when I was reading “Where the Red Fern Grows.” This is significant, because while reading “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” I was brought to the verge of tears at least three times. Every now and then, a story comes along that is so powerful, that you cannot believe you didn’t know about it; such is the story of Henrietta Lacks.

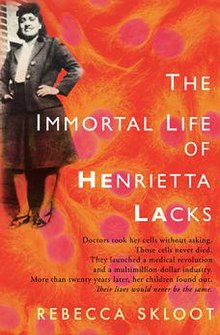

The Immortal Life tells the story of the HeLa cells, the most widely used cell line in medical research, and the woman, Henrietta Lacks, who was the donor. She was a poor African American woman who developed cervical cancer in the 1950s and went to the Johns Hopkins hospital for treatment. A sample of her tumor was provided to medical researchers without her knowledge or consent, and the cells go on to live forever in infamy, while she dies, largely in obscurity. Through the telling of this story, by author Rebecca Skloot, we find out the effects that the death of Henrietta and the immortal life of her cells have on her family. I will not go into great detail about the particulars of this book because I think everyone should put it on their reading list, but I will share with you why it made me cry.

In the afterward of the book, Skloot discloses the question she is most frequently asked when talking about Henrietta Lacks, “Don’t Doctors have to tell you when they use your cells in research?” The answer is no.

Earlier this year, I found a lump in my left breast. It wasn’t of much concern to me, I had found what turned out to be a cyst in my right the year before, but upon ultrasound of this one, the report stated: “Intermediate suspicion of malignancy, biopsy advised.” When I read that, my heart skipped a beat. There is a history of breast cancer in my family, and although I do everything in my power to lead a lifestyle that will minimize my risk, it is something I am acutely aware of. When Henrietta suspects that something is not quite right, and performs a self-examination, I recall tracing my fingers across my breast in the familiar pattern. In the section of the novel when Henrietta is being tested and is later diagnosed, I could feel a connection with her, spanning the 60 years between her appointment and mine, and her anxiety was mine.

When Henrietta’s cervix was biopsied and a tissue sample given to the researchers I was bothered. Something didn’t feel right. Skloot explains this in the afterward:

When you go to the doctor for a routine blood test or to have a mole removed, when you have an appendectomy, tonsillectomy or any other kind of ectomy, the stuff you leave behind doesn’t always get thrown out. Doctors, hospitals and laboratories keep it, often indefinitely.

She goes on to say that oftentimes, the paperwork you sign prior to a procedure has a section buried in the fine print discussing what may be done with your discarded tissues post-procedure. The procedure I had done, was as follows:

Ultrasound Needle Core Biopsy – An ultrasound needle core biopsy is a biopsy taken with a needle that is introduce into the breast by guiding the needle into the mass that was picked up on an ultrasound (sonogram). The radiologist will numb the area, put the needle into the skin of the breast and launch the needle into the mass under direct vision. The radiologist will show you how the needle enters the mass on the monitor. The needle is fired and tissue is retrieved, so-called core tissues, and this tissue is sent out to the pathologist for a reading on whether it is cancerous or not.

When I had my biopsy, they took 5 samples. It was an emotional procedure on many levels. I don’t live in the same state as my immediate family. I had spoken with my mother on the phone, but she couldn’t be there with me, the nurse was the woman who held my hand. I tried not to think about my grandmother’s mastectomy or my aunt’s death, but those ghosts haunted me as I waited the week it took to receive results. The tissue that was removed was an intimate part of me, and the idea that a researcher could just take it without my knowledge was disturbing. I pulled out my paperwork and tried to see what I had signed away, what did I give permission to someone to do with my samples? I couldn’t find anything.

As the story of Henrietta unfolded through Skloot’s journey, my heart went out to the family, but especially to this woman, an unsung hero who unknowingly gave her life to save millions. Her cells were responsible for the vaccine for polio, numerous studies on cancer research, yet ironically her children could not even pay for basic healthcare. I was reminded that it is sometimes easy to dissociate the human element from clinical research, but there is a person behind those stem cells, there is an anonymous name behind many of the medical advances we take for granted. How many other stories exist, how many Henriettas? This was a story that needed to be told.

While Henrietta’s tumor was an aggressive cancer that eventually killed her, the autopsy brought me to tears, my mass was thankfully benign. I don’t know Henrietta, I don’t know her family, but I feel forever connected to her and I am not the same person for having read this book. I thank God for her sacrifice, and I will donate to the foundation set up in her honor to assist African Americans seeking to pursue a degree in medical science.